Following my initiation in the driveway, the next phase of my driver training began a few weeks later when I started piloting the old truck ‘round and ‘round Dad’s gas station. I could even get it into a swift third gear in the lot circling the building. This was back in the day before self-serve gas stations, so every time I passed the pumps, it was ding, ding—over the hose that rung the bell inside to let Dad know that someone was wanting gas pumped. How he put up with that I’ll never know. Ding, ding.

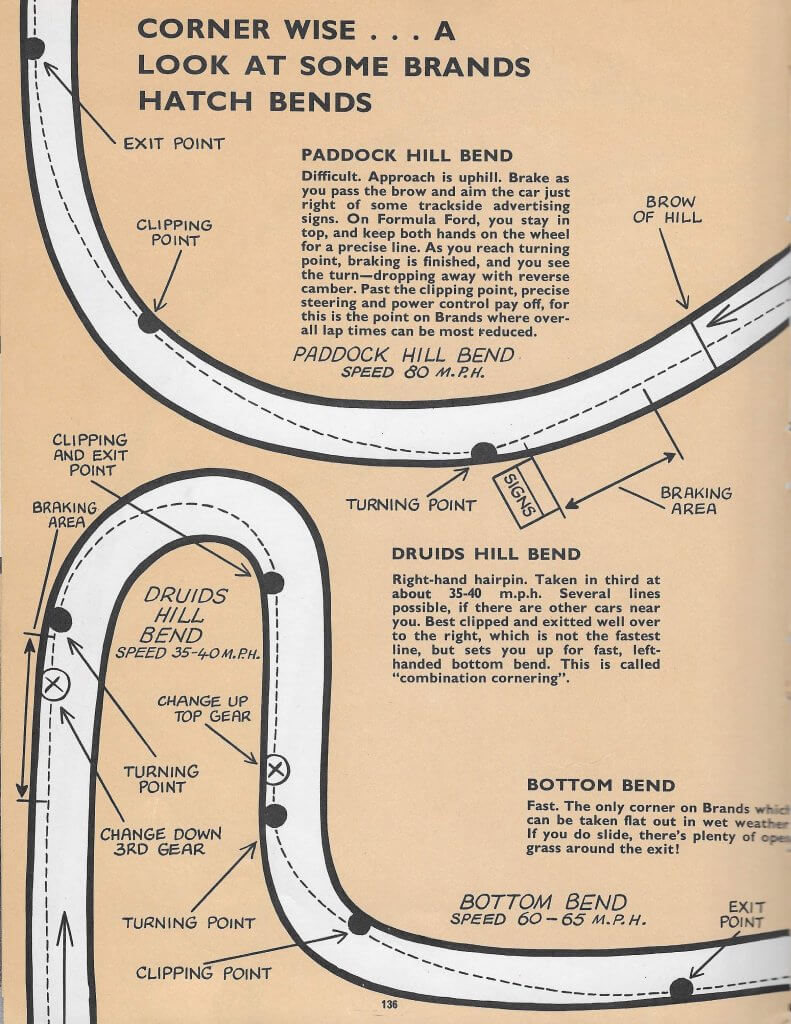

A few times through the years, Mitch and I talked Dad into taking us to the nearby go-kart track in Richmond. When I was about nine or ten, for Christmas I got a book all about racing in England; one of the chapters was about the line a race driver uses through a corner. The book even had an illustration of the Brands Hatch circuit with a line drawn describing the path that a racer would drive to turn the fastest lap time. In racing lingo, “the line” is the pathway the car follows; its purpose is to maximize the speed one can drive through each turn. Basically, the straighter the line, the faster one can drive. That’s what I remember to this day from that book (I still have it today, some 50 years later). It had a lasting impact on me.

A few times through the years, Mitch and I talked Dad into taking us to the nearby go-kart track in Richmond. When I was about nine or ten, for Christmas I got a book all about racing in England; one of the chapters was about the line a race driver uses through a corner. The book even had an illustration of the Brands Hatch circuit with a line drawn describing the path that a racer would drive to turn the fastest lap time. In racing lingo, “the line” is the pathway the car follows; its purpose is to maximize the speed one can drive through each turn. Basically, the straighter the line, the faster one can drive. That’s what I remember to this day from that book (I still have it today, some 50 years later). It had a lasting impact on me.

After reading that chapter hundreds of times and committing those curving arcs to memory, I’d practice my line around the go-kart track until I was faster than everyone else. I’d also test different lines on my bike off the street and into our driveway. I’d even think about the line as I circled Dad’s Chevron in the truck, apexing the back corner of the building and accelerating past the pumps. Ding, ding.

The morning of the day I went to take my driver’s license test, Dad suggested I try parallel parking. This was the only formal driver training he provided. We knew that parallel parking was one of the death-defying and lifesaving maneuvers I’d be tested on, so I tried it once. No problem. So off we went and a few hours later I came home with a piece of paper saying I was qualified to drive. It was anticlimactic, like getting a license to breathe.

Mom said I was obsessed. I continued to read everything I could get my hands and eyes on that had anything to do with driving. I’d go out and drive for three or four hours each day, practicing meshing together the steering wheel, pedals, and gear shifter. I’d imagine that someone was sitting next to me, and my goal would be that my passenger would never feel when one movement of the wheel or pedal began or ended—seamless was my objective. I was learning to dance with the car. Just like someone who practices breathing as part of meditation, I practiced driving. I got good.

Driving is my breathing. It’s what keeps me alive.

If you enjoyed this week’s story, share it with a friend.