Rolling out of pitlane at Mid-Ohio, lining up behind the pace car and thirty or so other cars in front of me, I’m warming the brakes and tires, preparing for the race start going green the second time by, getting used to the position of the pedals and steering wheel, noticing what I can see in the mirrors, checking the dash, memorizing the buttons on the center console, and mostly feeling for the way the car responds to my inputs.

“Green, green, green,” blasts into my earpieces. I stomp on the throttle, upshift to third, and tuck to the inside of the two cars in front of me going into the Carousel. I catch and pass another three cars this lap, then settle in to learn the car, a very-well-prepped Miata. Also, a car I’d never driven until I pulled out to begin the pace lap a few minutes ago. It’s time for me to learn where the limit is, while working in and around sixty-four other cars.

I had watched a few in-car video laps of one of its owners, Christian Maloof (a very fast driver!), in the car a few weeks earlier. That had given me an idea of what to expect, but I didn’t have time to take my time. I had to go get some fast lap times, right now.

Christian and a few other friends had asked me to join them for the Mid-Ohio Champcar race (8-hours on Saturday, and 7-hours on Sunday), and since I was already in Ohio doing some driver training not far from Mid-Ohio, it was a no-brainer to say yes. It would be fun spending time with good people, and get some wheel-to-wheel racing in. It wouldn’t be the fastest car I’d ever driven at Mid-Ohio, but that didn’t matter. To me, driving a car at or near its limits, and exercising my racecraft skills is what’s important. It, and the time with friends, is what’s fun.

At that moment, though, my goal was to learn to drive at the Miata’s limits as quickly as possible. Here’s how I approached it.

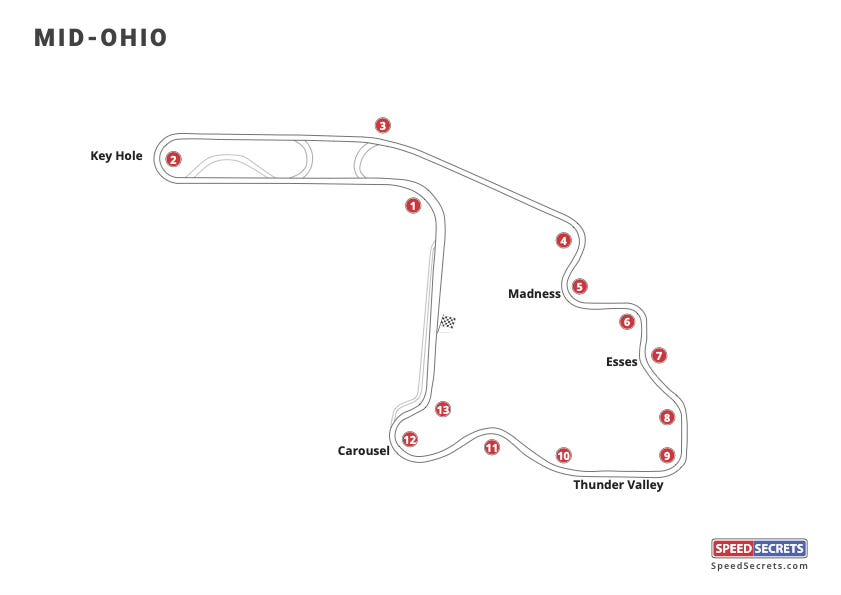

While every inch of Mid-Ohio’s fairly-recently-repaved surface was important, I knew that if I focused on two different corners first, that would pay off everywhere else:

Since we were running the “Pro course,” that meant the first two corners would be my main focus, and what I learned from them would carry over to how I drove the rest of the track.

Let me step back for a moment. I know Mid-Ohio fairly well, having raced there many times. The first time… well, it wasn’t a race. It was when I showed up there in 1990 for my Indy car rookie test, where John Andretti was looking over my shoulder (but not really over my shoulder, just keeping an eye on me and deciding whether I should get my Indy car license) while I learned the track and how to get up to speed in a car with about triple the horsepower of anything else I’d driven to date, all the while minding my manners amongst the twenty Indy car drivers with whom I was sharing the track. Guys like Bobby Rahal, Mario and Michael Andretti, Emerson Fittipaldi, Al Unser Jr., Rick Mears, and even A.J. Foyt.

I passed my Indy car rookie test, and added another great race track to the list of “favorites.” That day I had to learn Mid-Ohio and an Indy car at the same time. This time, only how to get the most out of a Miata, with not a single lap of practice prior to setting out on the pace lap. So, not much different!

Back to the present….

Turn 1

Initially, my focus was on leaving my braking later and later, and I did that until the rear of the car felt “nervous” as I entered the turn. By that, I mean the rear was starting to step out or oversteer. The fact that I was turning into this fast corner with a bit of brake on meant the front tires were loaded, the rears less so. I had transferred the Miata’s weight forward – too much forward – by braking late.

I had reached the car’s limits. If I had gone even half a MPH faster, it would have snapped into a big oversteer slide, trying spin. So, that’s it, right? I’d done my job of getting to the car’s limits, right? Nope. What I had done was create an artificially low limit. Sure, I was driving at the limit, but I needed to find a different way of driving to raise that limit.

Next, I braked about a car’s length earlier, but lighter. Immediately, I could tell that I was carrying more speed into towards the apex, and still getting back on throttle as early as I was the lap before. More of that, please!

For the next few laps, my focus was on braking lighter and lighter, until the point where I actually tried not touching the pedal at all. That was too much. I got through Turn 1 okay, but I was very late applying the throttle.

I should mention that I used a “report card” each lap between Turn 1 and the Keyhole: I noticed the RPMs just as I passed the entry into the Club course chicane, which told me whether my exit out of Turn 1 was better, worse, or no different.

Braking light, too light, not light enough… over the course of half a dozen laps, I felt like I had zeroed in on what seemed like the best compromise between corner entry speed, minimum speed, and my exit. I was using what I’d call a “2 pedal” entering Turn 1 (on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being threshold/maximum braking, I was barely brushing the brake), and doing that at least a car’s length earlier than I could have braked had I wanted to. “Early, light, balance” was my trigger, or mantra for Turn 1.

On to the Keyhole

Being a 180-degree corner, I was well-prepared to NOT drive this as a “slow in, fast out” type of corner, despite all the advice, instruction, tips, and finger wagging aimed at telling me that this is “the most important corner on the track because it leads onto the longest straight, so your exit speed is the priority.” Nope, not in my world. Instead, I’m thinking, “Fast in, faster out.”

Even though this is a tight corner, it’s long enough that I treated it in three phases:

I focused on carrying as much speed into the Entry, being patient in the Mid-corner phase, and launching the car out of the Exit (okay, it’s a Miata, so it’s never going to “launch” out of a corner; all the more reason to keep my Mid-corner min speed up).

I started with the brakes, since my exits were pretty good already (feeding in a Miata’s throttle in a way that drives the car out to the Exit curb is not hard). Makes sense, right? I found a comfortable place to begin braking (my BoB) around the 3-marker, and with each lap began releasing the brakes a tiny bit earlier, until it got so that I couldn’t quite get the car to rotate/turn in the way I wanted. At that point, I figured I was at the limit and couldn’t carry any more entry speed, right? Wrong, again. No, all this meant was that I hadn’t figured out how to make this entry speed — or more entry speed — work, yet.

Since the Miata would understeer when I carried too much entry speed, I needed to figure out how to get it to turn-in better. Timing and rate of release of the brakes. That’s the key. (If you thought “Miata” was the answer to most every question about what to drive on track, then “timing and rate of release of the brakes” is the answer to most any question about how to drive faster).

As part of the process I had used to find the limit, I had deliberately eased off, or released the brakes earlier and earlier to raise the corner entry speed. That also unloaded the front tires, and in fact, did lead to more understeer. So, it was time to undo some of that (not that that step in the process was wrong; it was needed to help me feel what the car would do when I entered too fast).

The next step was to move or shift the entire brake zone, from BoB to EoB, further into the corner. That fixed at least ninety percent of what I wanted to fix. My BoB was around the 2-marker, now, and my EoB was at least two car lengths further into the corner. The personal speed sensor that I store somewhere in my body (don’t ask where!) told me I was entering the Keyhole at least 3 MPH faster, now. That timing and rate of release of the brakes became critical to rolling that much more speed into the corner, and getting the Miata to turn.

With that extra corner entry speed, I had to adjust how much patience I needed in the middle of the corner, too. Without thinking, I noticed that I was waiting a fraction of a second after coming off the brake pedal, and doing nothing with the throttle; I was letting the car finish rotating, allowing it to aim towards the apex. Then, I’d tip in a tiny bit of throttle — no more than ten percent — just enough to keep the min speed, or momentum, up. This throttle tip was very short, almost a blip, but smoother. As quickly as I tipped into the throttle, I released it, causing the car to rotate again — just briefly. Then, I fed in the throttle, all the way.

Getting back to throttle felt almost as if it was a fraction of a second too early, to the point where I thought I might have to ease up before getting to the Exit curbing to avoid running out of track. But I didn’t. Rather than unwinding the steering to drive out to the Exit curbing, I used the throttle to drive the car out there — I had to unwind the steering because the throttle told me so, not the other way around.

Particularly in the Keyhole, I paid attention to the sound coming from the tires. I calibrated what I heard with what I felt, then checked that with my report cards. After a few laps, I knew what the tire noise sounded like when they were at the limit, under the limit, and over it. I used that sound to dial in the amount of steering angle I was asking the front tires for, knowing that the rears had to also follow them.

Throughout the rest of my stint, I fine-tuned both of these corners: the timing and rate of initial brake application, steering input, release of the brakes; how much patience was needed in the middle of the corners, while keeping the momentum up; and my throttle application (I figured more was almost always better). I used a “report card” on the back straight, just like I did between Turn 1 and the Keyhole, giving myself feedback as to what was working, and what wasn’t.

Everything that I learned from Turn 1 and the Keyhole was applied to other corners and sections of the track. For example, the way I drove Turn 1 told me what to do in Turn 11; driving the Carousel was not much different from the Keyhole; up through the Esses I knew that I could stay at full throttle, but I had to ask a lot of the front tires by turning the steering a lot; the sense of grip applied pretty much everywhere.

Rinse and repeat… but constantly adapting to changes in fuel load (weight), tire wear, ambient temperature, and traffic. And continually asking, “What can I do to be faster?”

During the first half of my one-hour-forty-five-minute stint, I might have looked at my lap times two or three times. It didn’t matter what they were, I wanted to go faster. In the second half of the stint, I did use the predictive timer to give some finer, more detailed feedback. But, between traffic and passing, and what I’d learned in the first dozen or so laps, I could predict what the timer was going to say almost before it did. In fact, I played a game with myself, seeing how close my guess of the lap time would be to the actual one that flashed up on the dash on the front straight. By focusing on what I felt and heard, and my internal speed sensor, I knew when I was at the limit, and when I wasn’t.

In endurance racing, being on the ragged edge is not necessarily the goal for every corner on every lap. Still, racing of every type and level is close these days, so leaving a few tenths of a second on the table is costing a team the chance of winning. I wanted to drive very near the limit at all times.

One reason for having a tenth or two (or more, depending on experience) of margin from the limit in races like this is to be ready to deal with the unexpected. And there were more than a few unexpected incidents in front and around me. In fact, the key was to expect the unexpected, and use my Vision Techniques; that paid off big time more than once (a story for another day and post).

All of this took about half a dozen laps. Sure, I could have sped things up by throwing the car into the corners and standing on the throttle sooner/harder, and just dealt with the consequences. That would have worked, too, and I might have gotten to the limit a little sooner. But this was not my car; it was owned by good friends who trusted me not to mess it up; it was the start of an 8-hour race; and there were other cars around me. My process might have taken two or three more laps to work through, but it paid off.

All of this while passing and being passed… that’s what makes racing so much fun! In fact, in a long race like this, one fast lap does not make the difference. No, it’s the average lap time, and my goal was to minimize the time I lost when passing another car, or if another car was passing me. Of course, I needed to start with a strong baseline, and that’s what the process of finding the limit at Mid-Ohio did for me.

P.S. – A big thanks to No Foo Racing… Christian, Mike, Martin, Joe, Rich, Ryan, and the support team for letting me come race and play with them.

P.S.S. – Getting up to speed, and learning to drive the limit, is top of mind for me right now because I’m preparing for the Total Car Control Masterclass that I’m doing in mid-October (and recording). There’s nothing like being able to do hands-on research and review of the content that I’m teaching. See, none of this was about having fun, it was all work, and no play…. 🙂